Studying Lung Conditions in a Lab Dish

How do you study children and adults who suffer from asthma, allergies or respiratory diseases? Without direct access to the lung for experiments, researchers find it challenging to study the molecules and cells that cause these conditions.

But Benaroya Research Institute (BRI) and Seattle Children’s Research Institute (SCRI) scientists have tackled this problem by creating a “lung in a dish” and conducting exciting new experiments. Lead investigators are Steven Ziegler, PhD, director of the BRI Immunology Research Program and Academic Affairs, and Jason Debley, MD, of SCRI. They have also collaborated with BRI’s Erik Wambre, PhD, on allergies and Tom Wight, PhD, on the connecting tissue of the lung.

Model System

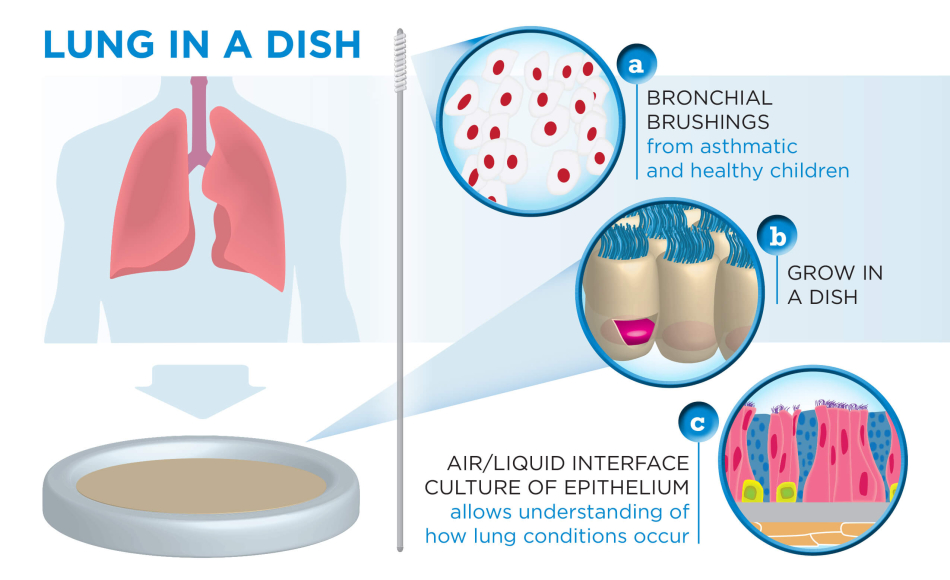

“We’ve created a model system of the human lung in a laboratory dish,” says Dr. Ziegler. “We can replicate the environment of what you’d find in a lung by taking bronchial brushings from children and growing the cells in a special tissue culture system called air-liquid interface culture, which mimics what is seen in the airways.” Through SCRI, scientists have samples of cells from 200 children, 75 children with asthma, 50 who are at risk of developing asthma and 75 who are healthy.

An important part of the experiments is studying the lung epithelium. It is the cell layer in the lungs that serves as the interface between the inside of the lung and the outside environment. “It’s a barrier for bacteria and viruses in the lung, but it’s also a sensor. It’s a smart barrier,” explains Dr. Ziegler. “We’ve learned that it senses potential threats and determines whether or not to mount a response. For individuals prone to allergy and asthma, the epithelium incorrectly initiates immune responses to pollen or other innocuous environmental allergens.” The immune cells will then release chemicals which cause sneezing, itching in the nose and other reactions.

In addition, Dr. Debley says, “The epithelial response to infection and injury in asthma seems to be dysfunctional, sending signals to other cells in the lung that lead to airway scarring and narrowing, and ultimately a decline in lung function. Our model system using human cells from carefully characterized children with and without asthma is greatly expanding our understanding of mechanisms that drive childhood asthma, which we are optimistic will lead to novel therapies for this common condition.”

With the “lung in the dish” these scientists can

-

Understand how cells in the epithelium and the immune system communicate closely with one another.

-

Test how the epithelium responds to different viruses and bacteria.

-

Visualize how the immune system mistakenly responds to allergens to cause allergies.

-

Observe how the structure of the lung changes with disease, such as the lung getting stiffer, which can cause breathing trouble.

-

Manipulate genes in the epithelia cells to see which ones play a role in health and disease.

-

Observe the difference in gene expression patterns from a healthy person and one with asthma.

-

Understand how the surrounding tissue of the epithelia plays a role in healing.

Future studies may include investigating more diseases of the lung, testing toxicity of environmental pollutants and researching respiratory drugs.

Immuno-what? Hear the latest from BRI

Keep up to date on our latest research, new clinical trials and exciting publications.