New Therapies

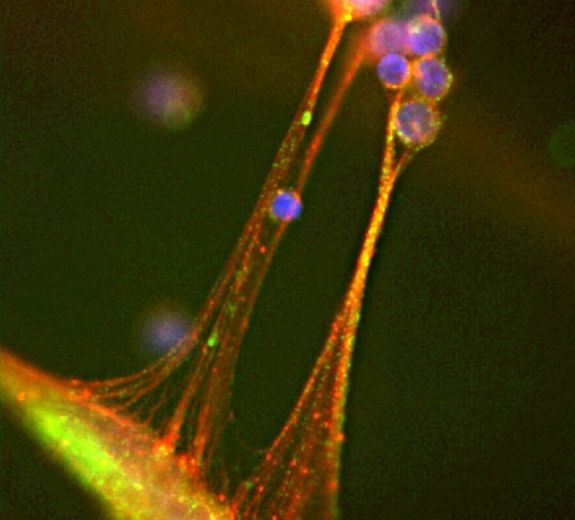

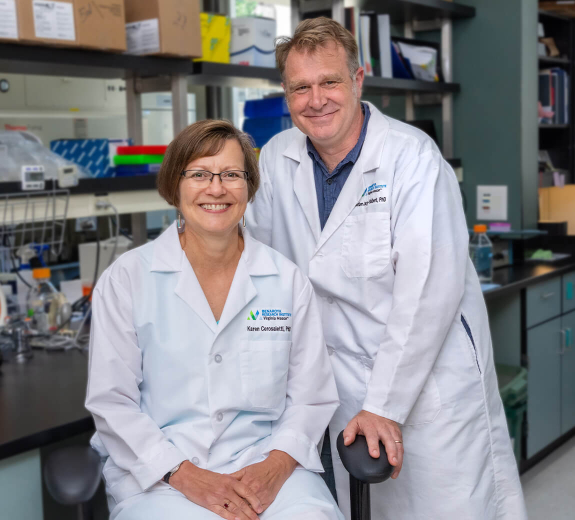

Dr. Cerosaletti has identified a different gene involved in lupus: BANK1. This gene plays a role in immune cells called B cells. Many B cells make tiny proteins called antibodies, and some of these antibodies attack healthy cells, causing lupus.

Dr. Cerosaletti has shown that BANK1 may increase the number of B cells that make antibodies, especially in people with lupus who have a particular BANK1 variant. She is using her DOD grant to study how BANK1 spurs B-cell growth — planning to eventually test drugs that could block this process, to slow or even prevent lupus.

“There’s only one drug that was developed specifically for lupus,” Dr. Cerosaletti says. “This research could open the door to more treatments that help more people.”

Hope for a Cure

Toni is all too aware that there’s only one drug developed for lupus, because it doesn't work for her. That’s why her new mission is helping others who have the disease.

“In the military, you always have a purpose,” she says. “Now lupus is my purpose.”

Toni leads a lupus support group in Arizona, advocates for research funding and sits on the DOD’s Peer Review Panel for lupus research.

“The people developing these drugs might not think about how a drug that causes hair loss would impact a 20-year-old, or that a medication that causes weight gain might cause a middle schooler to get bullied,” she says. “The panel lets patients like me voice these concerns.”

The DOD-fueled research gives Toni hope.

“I’m excited that there will be better treatments in my lifetime,” she says, “and maybe even a cure.”