With a newly awarded $4 million grant from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, BRI and SCRI will now focus on using their novel approach to generate an engineered T cell product that can be used in a future first-in-human clinical trial. This exciting momentum builds upon $3 million in previous funding by Helmsley and brings the teams one step closer to effectively regulating the immune response and preventing T1D from developing in children.

Engineering T Cells to Prevent Type 1 Diabetes Takes Next Step Towards Human Clinical Trial

Over the last four years, Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason Franciscan Health (BRI) and Seattle Children’s Research Institute (SCRI) have been developing a novel approach to engineer a person’s own immune cells to target and treat type 1 diabetes (T1D), with the goal of eliminating the need for insulin injections. Currently, people with T1D must inject themselves with insulin in order to stay alive.

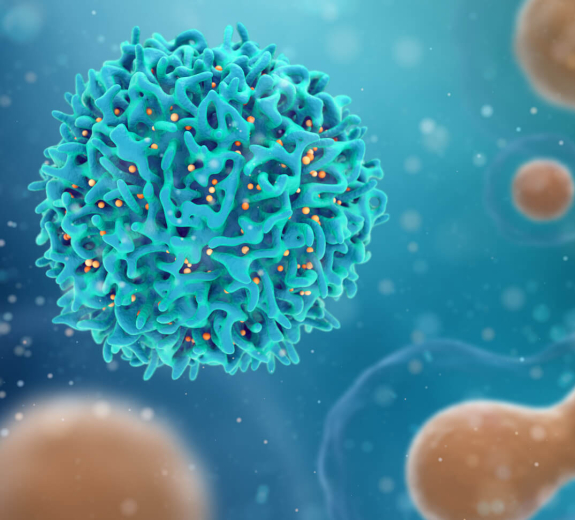

T Cells in the Body

This research focuses on the body’s T cells (white blood cells that fight off infection). In T1D, a particular type of T cells called effector T cells attack insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, called islet cells. This attack destroys the islet cells leading to no or reduced insulin production.

A healthy immune system has a mechanism of stopping such self-destruction, in the form of another kind of T cell called regulatory T cells, or Tregs. When Tregs are not functioning properly, this important brake on the pancreas-destroying effector T cells does not occur. Over time, a person is likely to develop diabetic symptoms and illustrates why someone living with T1D, whose immune system is imbalanced, has to take daily insulin.

Collaboration to Course-Correct T Cell Response

BRI and SCRI have been collaborating for years on this research. BRI President Jane Buckner, MD and her team are experts at finding and studying the effector and regulatory T cells in T1D. In this study they will use that skill to identify and test T-cell receptors, which are critical to instruct a Treg to inhibit an immune response targeting the pancreas, while SCRI’s David Rawlings, MD, Director of the Center for Immunity and Immunotherapies and his lab have the expertise to engineer T cells that function normally. Both teams are generating engineered cells and then testing their function.

The first step in the process is to isolate T cells from the patient’s body. Next, the cells are engineered and reprogrammed to function as normal Treg (the regulatory T cells that alleviate the attack). The engineered regulatory-like T cells (edTreg) are then transferred back into the patient to go to work, suppressing the overactive immune response and restore balance to the functioning cells.

“A healthy immune system requires regulatory T cells to balance the attack of effector T cells,” Dr. Rawlings said. “Regulatory T cells tell the effector T cells to calm down and limits damage to tissues like the pancreas.”

“We want to identify T-cell receptors that will create engineered Treg that will go to and protect the pancreas. This type of therapy could then be used to stop the destruction of cells that produce insulin in the pancreas to slow the progression and ultimately prevent type 1 diabetes,” said Dr. Buckner.

Research Promise

This research approach treats T1D by targeting the root issue, rather than covering up or relieving the disease’s symptoms. It would be a game-changer for the T1D community.

To get there, BRI and SCRI must understand if these engineered T cells are safe and effective in humans, which requires clinical trials. The Helmsley grant covers the next three years of research, in which time Drs. Buckner and Rawlings believe they can complete preclinical studies and submit the necessary Investigational New Drug Application to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in order to gain approval to open a phase 1 clinical trial.

“We are excited about this next phase of research,” said Dr. Buckner. “We believe within the next five years we’ll be prepared for clinical trials. This will open the door to an abundance of insights on type 1 diabetes and how to treat it.”

This news falls on the heels of the research partnership’s recent paper published in Science Translational Medicine, which shows how they developed these same engineering techniques to target the FOXP3 gene in human T cells and develop a functional Treg-like cell product. A landmark study that lends proof to how this T cell engineering approach can also work for T1D.

Immuno-what? Hear the latest from BRI

Keep up to date on our latest research, new clinical trials and exciting publications.